You Have New Patients!

Patient 1

You meet a 40-year-old man in the ED, held by three security staff, looking diaphoretic and agitated, having tachycardia, and pointing vaguely in a direction as if interacting with imaginary people. When you try to assess him, he appears to be confused and disoriented and smells of alcohol. Over 6 hours, the patient has tremulousness, gets easily frightened, and gets further uncooperative for examination.

Patient 2

You evaluate an 80-year-old woman in the ICU. She has a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression, and a stroke two years ago. She was admitted due to increased sleepiness, urinary and fecal incontinence for one week, and difficulty recognizing people. Before her admission, she was active and independent, had a reasonably good memory, and could manage household responsibilities. On physical examination, her eyes remain spontaneously closed but open with audible stimuli, and she is disoriented to time, place, and person.

Introduction

Delirium is a rapidly developing clinical syndrome characterized by alterations in attention, consciousness, and awareness, with a reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. It commonly occurs in the elderly, with an incidence reported in 10% to 30% of patients hospitalized for medical illnesses and up to 50% following high-risk procedures [1].

This condition is also referred to as acute organic brain syndrome, characterized by rapid onset, diurnal fluctuations, and a duration of less than six months. Its behavioral presentation can vary, with the following manifestations.

Hyperactive Delirium: Patients present with increased agitation and heightened sympathetic activity. They may exhibit hallucinations, delusions, and combative or uncooperative behavior.

Hypoactive Delirium: Patients display increased somnolence and reduced arousal. The diagnosis is often overlooked due to its subtle clinical manifestations, which are frequently mistaken for fatigue or depression. This subtype is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

Mixed Presentation: Patients fluctuate between hyperactive and hypoactive delirium.

Delirium tremens (DT) is the most severe form of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and can be fatal. It typically occurs within 2 to 4 days following complete or significant abstinence from heavy alcohol consumption in approximately 5% of patients, with mortality rates as high as 50%. Alcohol functions as a depressant, similar to benzodiazepines and barbiturates, and affects serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA A) receptors, leading to tolerance and habituation.

Delirium is a dangerous and often preventable condition, associated with significant costs and increased morbidity and mortality. Among delirium patients presenting to the emergency department, there is a 70% increased risk of death within six months. In the ICU, delirium is linked to a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of overall mortality. Prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of the underlying cause, along with well-coordinated care, are essential to improve patient outcomes.

General Approach

The diagnosis of delirium is primarily clinical and relies on careful history-taking, mental status examination, and detailed cognitive assessment. While laboratory and diagnostic tests may assist in identifying the underlying etiology, the initial evaluation should focus on addressing reversible causes. Life-threatening conditions must be promptly recognized, requiring rapid intervention and stabilization.

Differential Diagnoses

Delirium can present with symptoms that may be easily mistaken for mental illness, such as acute aggression, irritability, restlessness, and visual hallucinations [1]. Delirium mimics may include psychosis or mood disorders in the case of hyperactive delirium, and depression in the case of hypoactive delirium.

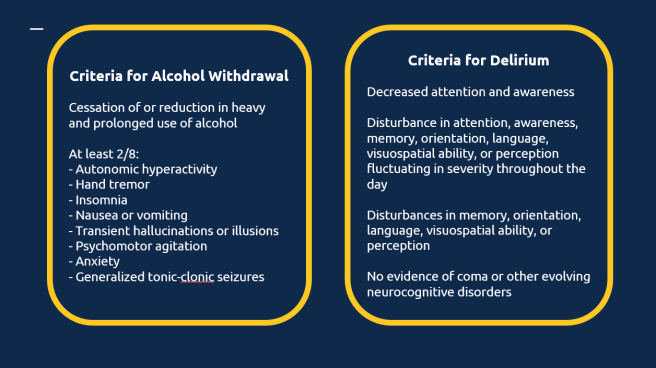

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) guidelines [2], a definite diagnosis of delirium requires the presence of symptoms (mild or severe) in each of the five described areas. These include: impairment of consciousness and attention (ranging from clouding to coma, with a reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention), global disturbance of cognition, psychomotor disturbances, disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle, and emotional disturbances.

Delirium

Delirium typically presents with an acute onset and progresses rapidly. It often resolves completely with treatment of the underlying cause. Clinically, it is characterized by fluctuating levels of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, worsening symptoms in the evening (a phenomenon known as sundowning), and transient visual hallucinations. Delirium carries significant risks, including high mortality due to the underlying medical condition, as well as increased risk of falls, injuries, exhaustion, or aggression.

Dementia

Dementia has an insidious onset and follows a chronic, progressive course marked by continuous deterioration over time. Key clinical features include memory disturbances, changes in personality or behavior, apathy, and apraxia. Individuals with dementia are at risk of falls, neglect, abuse, agitation, and wandering away from their safe environments.

Depression

Depression typically has a slow onset and an episodic course, with periods of remission and recurrence. Symptoms include a persistently depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, reduced energy, feelings of hopelessness, disturbances in sleep and appetite, difficulties with concentration, and pervasive negative thoughts, often accompanied by guilt. The associated risks include suicide, deliberate self-harm, neglect, and agitation.

Psychosis

Psychosis usually begins insidiously and follows a progressive course punctuated by episodes of exacerbation. Clinical features include delusions, auditory hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, social withdrawal, apathy, avolition (lack of motivation), and impaired reality testing. Psychosis poses risks such as aggression, harm to others, and non-adherence to treatment, which can exacerbate the condition further.

History and Physical Examination Hints

It is of paramount importance to obtain a detailed corroborative history regarding the onset, course, and progression of the illness, along with performing a thorough physical and neurological examination of the patient. A biopsychosocial formulation must identify the predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating causes of delirium [1].

The mnemonic “I WATCH DEATH,” developed by Dr. M.G. Wise in 1986, is a valuable tool for clinicians to screen for possible causes of delirium [3].

I – Infections: Infections are a common cause and can include conditions such as sepsis, urinary tract infections, encephalitis, and meningitis.

W – Withdrawal: Sudden withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, sedatives, or drugs can lead to significant medical complications.

A – Acute Metabolic Disturbances: Issues such as electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hyponatremia) and organ failure, such as hepatic or renal failure, can significantly disrupt normal physiological functions.

T – Trauma: Physical injuries, including head trauma and falls, are notable causes that may lead to further complications like bleeding or swelling.

C – CNS Pathology: Central nervous system disorders such as stroke, hemorrhage, seizures, or the presence of space-occupying lesions like tumors can have profound impacts on a patient’s condition.

H – Hypoxia: A lack of adequate oxygen supply, often due to anemia or hypotension, can result in significant systemic effects.

D – Deficiencies: Nutritional deficiencies, particularly a lack of essential vitamins and minerals like thiamine, can result in various clinical symptoms.

E – Endocrine Disorders: Hormonal imbalances, including thyroid storm and hyperglycemia, can disrupt metabolic processes and cause severe systemic effects.

A – Acute Vascular Events: Sudden vascular events, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, require prompt identification and management due to their life-threatening nature.

T – Toxins or Drugs: Exposure to industrial poisons, carbon monoxide, or drugs with anticholinergic properties can have toxic effects on the body.

H – Heavy Metal Poisoning: Exposure to heavy metals such as lead and mercury can lead to chronic toxicity and require specific interventions.

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing delirium, especially in vulnerable populations:

Age: Both elderly individuals and young children are at heightened risk due to their increased susceptibility to physiological and cognitive changes.

Recent Hospitalizations: Hospital stays, particularly those involving medical illnesses or surgical procedures, can act as significant stressors and predispose individuals to delirium.

Pre-existing Brain Conditions: Conditions like brain damage or dementia further increase the risk, as they impair cognitive resilience.

Chronic Medical Disorders: Long-term health conditions often contribute to a state of chronic physiological stress, increasing the likelihood of delirium.

Sensory Deprivation: Impairments in vision or hearing can lead to sensory deprivation, which may exacerbate confusion and disorientation.

Substance Use Disorders: Alcohol or drug use disorders are major contributors to the onset of delirium, particularly during withdrawal periods or intoxication.

Medications: The use of psychotropic medicines and polypharmacy (simultaneous use of multiple medications) heightens the risk of delirium due to potential drug interactions and side effects.

History of Delirium: Individuals with a previous history of delirium are more likely to experience recurrent episodes, particularly if the underlying risk factors persist.

Malnutrition: Poor nutritional status can exacerbate vulnerability to delirium by impairing metabolic and neurological functions.

Burns: Severe burns create systemic inflammation and stress, which can predispose individuals to delirium.

Screening tools for delirium, such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [4] and the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [5], are valuable for early identification and intervention. These tools can also be used to monitor clinical improvement when performed repeatedly during the course of the illness.

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) includes four key features to identify delirium. A diagnosis of delirium requires the presence of Features 1 and 2 and either Feature 3 or Feature 4:

Feature 1 – Acute Onset and Fluctuating Course: There is evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline.

The abnormal behavior fluctuates throughout the day, tending to come and go or change in severity.

Feature 2 – Inattention: The patient has difficulty focusing attention, is easily distractible, or cannot keep track of what is being said.

Feature 3 – Disorganized Thinking: The patient demonstrates disorganized or incoherent thinking, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable switching between subjects.

Feature 4 – Altered Level of Consciousness: The patient’s consciousness level deviates from “alert.” It may range from hyperalert (vigilant) to lethargy, stupor, or coma.

The CAM is a widely used, reliable tool with high sensitivity (94–100%) and specificity (90–95%). It enables quick and accurate identification of delirium, facilitating early intervention to manage underlying causes and improve patient outcomes.

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) Instrument:

- Acute Onset:

- This involves an abrupt change in the patient’s mental status, which is evident when comparing their current state to their baseline cognitive function. This change may be noticed by family members, caregivers, or clinicians and is typically indicative of an acute underlying medical issue or condition.

- Inattention:

- 2A: The patient has difficulty concentrating or paying attention. This may manifest as being easily distracted, unable to follow conversations, or losing track of what is being discussed.

- 2B: If inattention is present, the behavior often fluctuates over time, meaning it can improve or worsen during an assessment or throughout the day.

- Disorganized Thinking:

- The patient’s thought process appears chaotic or incoherent. They may exhibit rambling, irrelevant speech, an illogical sequence of ideas, or rapid, unpredictable topic changes during a conversation. This suggests a loss of organized, goal-directed thinking.

- Altered Level of Consciousness:

- The patient’s alertness deviates from normal. This can range from:

- Alert (normal): Fully awake and responsive.

- Vigilant (hyperalert): Overly sensitive to stimuli, easily startled, or hypervigilant.

- Lethargic: Drowsy but easily aroused.

- Stupor: Difficult to arouse, with limited responsiveness to stimuli.

- Coma: Unarousable and non-responsive.

- The patient’s alertness deviates from normal. This can range from:

- Disorientation:

- The patient is confused about time, place, or identity. They may incorrectly believe they are in a different location, misjudge the time of day, or demonstrate an inability to recognize familiar surroundings or people.

- Memory Impairment:

- Memory issues are evident when the patient cannot recall recent events, forgets instructions, or struggles to remember details of their hospital stay or interactions.

- Perceptual Disturbances:

- The patient may experience hallucinations (e.g., seeing or hearing things that aren’t present), illusions (misinterpreting real stimuli, such as mistaking a shadow for an object), or misinterpretations (believing something benign, such as a coat rack, is threatening).

- Psychomotor Disturbances:

- 8A (Agitation): The patient may exhibit increased motor activity, such as restlessness, repeatedly picking at bedclothes, tapping their fingers, or making frequent, sudden movements.

- 8B (Retardation): Alternatively, the patient may show decreased motor activity, appearing sluggish, staring into space, staying in the same position for extended periods, or moving very slowly.

- Altered Sleep-Wake Cycle:

- Disturbances in the patient’s sleep pattern are evident. They may experience excessive daytime sleepiness coupled with difficulty sleeping at night, or their sleep-wake rhythm may become reversed.

Associated Features

Certain medical conditions can present with a range of distressing symptoms and features:

Hallucinations and Illusions: Patients may experience vivid and often frightening visual or auditory hallucinations. Additionally, tactile hallucinations, such as the sensation of insects crawling on the body, can occur, adding to their distress.

Autonomic Disturbances: Marked autonomic instability is common and may include symptoms such as tachycardia, fever, hypertension, sweating, and pupillary dilation.

Psychomotor and Coordination Issues: Psychomotor agitation and ataxia (lack of muscle coordination) are frequently observed, contributing to physical instability and difficulty performing tasks.

Sleep Disturbances: Insomnia is a notable feature, often accompanied by a reversal of the sleep-wake cycle, further exacerbating cognitive and physical impairments.

It is crucial to obtain a detailed history of the patient’s premorbid personality, as this helps establish their baseline cognitive state and allows the clinician to determine the magnitude of cognitive deterioration. Patients with fluctuating levels of consciousness may experience rapid shifts in their activity levels, ranging from extreme psychomotor excitement to sleepiness during an interview [1].

The Mental State Examination (MSE) should include an assessment of mood (e.g., apathy, blunted affect, emotional lability), behavior (e.g., withdrawn, agitated), activity levels, thoughts (e.g., delusions), and perceptions (e.g., hallucinations, illusions). A brief cognitive assessment may utilize the COMA framework, which evaluates Concentration, Orientation, Memory, and Attention.

Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)

The CIWA-R is a tool designed to standardize the assessment of withdrawal severity in patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal. This instrument is particularly useful for guiding treatment decisions and ensuring appropriate management of symptoms.

Alcohol withdrawal delirium progresses through distinct stages, including:

- Tremulousness or Jitteriness: Occurs within 6–8 hours of cessation or reduction in alcohol use.

- Psychosis and Perceptual Symptoms: Develops between 8–12 hours, marked by hallucinations and disorganized thinking.

- Seizures: Typically occur within 12–24 hours of withdrawal.

- Delirium Tremens: The most severe stage, manifesting within 24–72 hours and potentially lasting up to one week. This phase is characterized by confusion, autonomic instability, and significant risk of complications.

The CIWA-R plays a critical role in monitoring these stages and ensuring timely interventions to mitigate risks associated with alcohol withdrawal.

Click here to download full CIWA-R evaluation form.

Diagnostic Tests and Interpretation

Relevant laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging are recommended to assess the underlying etiology of delirium. Routine workups for electrolytes, kidney and liver function, and pregnancy tests for women are advised. Blood tests can help identify medical conditions that may mimic delirium, such as hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (via blood sugar levels) or thyrotoxicosis (via thyroid profile). Test results indicative of long-term heavy alcohol use, such as evidence of cirrhosis or liver failure on ultrasound, macrocytic anemia, and elevated liver transaminase levels—particularly gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase—can aid in reaching the correct diagnosis [6].

Positron emission tomographic (PET) studies have suggested a globally low rate of metabolic activity, particularly in the left parietal and right frontal areas, in otherwise healthy individuals withdrawing from alcohol. Diffuse slowing of the background rhythm has been observed on electroencephalography (EEG) in patients suffering from acute delirium, except in cases of alcohol-related delirium tremens, which typically exhibit fast activity [1].

Management

Delirium is a medical emergency requiring immediate hospitalization to correct the underlying causes while minimizing risks associated with behavioral symptoms, aggression, dehydration, falls, and injury. High-potency antipsychotics in low doses are recommended for managing aggression and behavioral symptoms. Haloperidol (Haldol) has been extensively studied for reducing agitation due to delirium [7]. Evidence also supports the use of other atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone. Aripiprazole has demonstrated significant benefit in the complete resolution of hypoactive delirium [8].

The use of benzodiazepines should be restricted to cases of delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal. If liver function is not impaired, a long-acting benzodiazepine, such as chlordiazepoxide or diazepam, is preferred and can be administered orally or intravenously. In cases of reduced liver function, lorazepam may be given orally or parenterally as needed to stabilize vital signs and sedate the patient. These medications should then be tapered gradually over several days with close monitoring of vital signs. Anticonvulsants like carbamazepine and valproic acid are also effective in managing alcohol withdrawal. However, antipsychotics should be avoided in such cases due to their potential to lower the seizure threshold. Chronic alcoholics are at high risk of vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, which can predispose them to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (characterized by memory problems, confabulation, and apathy), cerebellar degeneration, and cardiovascular dysfunction. To mitigate this risk, such patients should receive 100 mg of thiamine intravenously before glucose administration.

Environmental modification strategies are particularly useful for managing delirious patients. These include providing well-illuminated rooms with good ventilation and reorientation cues such as calendars and alarm clocks. Assigning patients to a room near the nursing station allows for closer monitoring, ideally with the presence of a family member or close friend. In severe cases with agitation or injury risk, one-on-one supervision is advisable to ensure patient safety [1]. Both under-stimulation and overstimulation should be avoided. The use of physical restraints should be considered a last resort, with frequent monitoring and discontinuation as soon as possible. Psychoeducation for family members and caregivers is crucial to manage expectations and improve their involvement in the patient’s care [2].

Special Patient Groups and Other Considerations

Elderly patients are at high risk of altered mental status, and studies have recommended advanced age as an independent risk factor warranting screening of this vulnerable group through structured mental state assessments. It is important to recognize that behavioral manifestations of this magnitude should not be regarded as a normal part of the aging process. Dementia must be carefully differentiated from delirium in the geriatric population, as dementia typically presents with an insidious onset and a progressive course [3].

Other risk factors in the elderly that require attention include underlying neurological causes, multiple medical comorbidities, polypharmacy, poor drug metabolism, and sensory limitations [9]. Medications for elderly patients should be initiated at lower doses, and potential drug interactions must be considered whenever new medications are introduced.

The pediatric age group may present with nonspecific symptoms of acute onset, necessitating a detailed history and physical examination to rule out causes such as fever, injury, or foreign objects. Pregnancy, meanwhile, may predispose healthy women to medical conditions such as diabetes, venous thromboembolism, strokes, and eclampsia [9].

When To Admit This Patient

Admission decisions for confused patients or those undergoing alcohol withdrawal require a multifaceted approach that prioritizes accurate diagnosis, evidence-based treatment, and legal considerations. These decisions should aim to address the immediate medical needs while planning for long-term recovery and safety.

Admitting a confused patient requires careful evaluation of the underlying causes, as confusion can result from various conditions such as dementia, delirium, or depression, each requiring distinct management strategies [10]. Delirium, an acute confusional state, is particularly prevalent in older adults and often develops rapidly with fluctuating severity [11]. It is essential to determine whether the confusion is acute, chronic, or a combination of both, as this distinction guides the initial management plan [11].

Risk factors for acute confusion include admission from non-home settings, lower cognitive scores, restricted activity levels, infections, and abnormal laboratory values. These indicators suggest frailty and may also point to underlying chronic undernutrition or dehydration [12]. Early recognition and appropriate management are crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality, as confusion is often misdiagnosed or undertreated in hospital settings [10].

Furthermore, legal and ethical challenges, such as evaluating a patient’s decision-making capacity and ensuring that any necessary restraints are lawful and ethical, must be addressed to avoid infringing on the patient’s rights [13]. A comprehensive assessment of cognitive and physical status, coupled with an understanding of legal considerations, is essential for developing a management plan that effectively addresses the specific causes and risks associated with confusion [11-13].

Disposition decisions for confused patients, including those undergoing alcohol withdrawal, require a comprehensive and systematic approach that integrates accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and continuous monitoring. Alcohol withdrawal can result in severe complications, such as seizures and delirium tremens, with mortality rates ranging from 1% to 30%, depending on the quality of treatment provided [14]. Prompt identification and management are critical, often involving benzodiazepines like diazepam to alleviate symptoms and prevent progression to life-threatening conditions [15]. Management becomes particularly challenging in critically ill patients, as incomplete alcohol consumption histories and the need for adjunctive medications beyond benzodiazepines complicate care during severe withdrawal or delirium tremens [16].

Emergency departments frequently encounter substance use disorders; however, less than half of alcohol-related issues are identified, highlighting the importance of comprehensive assessments and evidence-based interventions. Effective disposition decisions rely on early identification, tailored treatment strategies, and ongoing evaluations to ensure patient safety and recovery.

Clinical Pearls

- Alcohol Withdrawal Characteristics: Alcohol withdrawal can begin within hours to days following heavy and prolonged alcohol use. A key feature of alcohol withdrawal is autonomic hyperactivity, which may present as increased heart rate, sweating, tremors, and other signs of sympathetic nervous system overactivity.

- Overlap with Sedative-Hypnotic Withdrawal: The diagnostic criteria and symptoms for alcohol withdrawal are identical to those for sedative-hypnotic withdrawal. This similarity highlights the importance of carefully assessing a patient’s history of substance use to guide appropriate management.

- Treatment Approaches:

- Delirium Due to General Medical Conditions: The preferred treatment is low doses of high-potency antipsychotics, which help manage symptoms without excessive sedation or complications.

- Alcohol Withdrawal: Benzodiazepines remain the first-line treatment to alleviate withdrawal symptoms and prevent complications such as seizures or delirium tremens. In cases where hepatotoxicity is a concern, short-acting benzodiazepines like lorazepam are preferred due to their safer profile in patients with compromised liver function.

- Hallucinations and Diagnosis: Visual hallucinations are more characteristic of delirium than of primary psychiatric disorders. This distinction is critical in differentiating between medical and psychiatric causes of altered mental status.

Revisiting Your Patient

Patient 1

The patient presents with the smell of alcohol and clinical features consistent with delirium tremens, a severe manifestation of alcohol withdrawal.

Further Management: The patient should be treated promptly with a benzodiazepine, starting with high doses and tapering as recovery progresses. Chronic alcohol users are commonly deficient in vitamin B1 (thiamine), which can result in dementia and cognitive impairments. Thiamine replacement should be administered prior to glucose to prevent the development of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome [17].

Patient 2

The patient is unresponsive to stimuli, disoriented, and has multiple medical conditions, which is suggestive of delirium due to a general medical condition, hypoactive type.

Further Management: Immediate steps should include ensuring 24-hour supervision, investigating the underlying cause, and implementing reorientation strategies. Low-dose antipsychotics have been recommended, with studies reporting complete resolution of symptoms with the use of aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics [18].

Author

Mehnaz Zafar Ali

Consultant Psychiatrist, Al Amal Psychiatry Hospital, Emirates Health Services, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Listen to the chapter

References

- Gleason OC. Delirium. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(5):1027-1034.

- World Health Organization. Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders. In: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed. 2016:182-188.

- Gower LE, Gatewood MO, Kang CS. Emergency department management of delirium in the elderly. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(2):194-201. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.10.6654.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

- Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941.

- Chan M, Moukaddam N, Tucci V. Stabilization and management of the acutely agitated or psychotic patient. In: Cevik AA, Quek LS, Noureldin A, Cakal ED, eds. International Emergency Medicine Education Project. 1st ed. iEM Education Project; 2018:452-457.

- Smit L, Slooter AJ, Devlin JW, et al. Efficacy of haloperidol to decrease the burden of delirium in adult critically ill patients: the EuRIDICE randomized clinical trial. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):413. doi:10.1186/s13054-023-04692-3.

- Lodewijckx E, Debain A, Lieten S, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for hypoactive delirium in adult patients: a brief report of the literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(6):1313-1316.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.037.

- Cetin M, Oktem B, Canakci ME. Altered mental status. In: Cevik AA, Quek LS, Noureldin A, Cakal ED, eds. International Emergency Medicine Education Project. 1st ed. iEM Education Project; 2018:111-121.

- Winstanley L, Glew S, Harwood RH. A foundation doctor’s guide to clerking the confused older patient. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2010;71(5):M78-M81. doi:10.12968/hmed.2010.71.Sup5.47934.

- Andrews H, Clarke A, Parmar S, et al. You’ve been bleeped: the confused patient. BMJ. 2015;351:h3266. doi:10.1136/sbmj.h3266.

- Wakefield BJ. Risk for acute confusion on hospital admission. Clin Nurs Res. 2002;11(2):153-172. doi:10.1177/105477380201100205.

- Lyons D. The confused patient in the acute hospital: legal and ethical challenges for clinicians in Scotland. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2013;43(1):61-67. doi:10.4997/jrcpe.2013.114.

- Thanyanuwat R. Patients who suffer from alcohol withdrawal and disorientation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(2):78-83.

- Thompson WL. Management of alcohol withdrawal syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138(2):278-283. doi:10.1001/archinte.1978.03630260068019.

- Sutton LJ, Jutel A. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome in critically ill patients: identification, assessment, and management. Crit Care Nurse. 2016;36(1):28-40. doi:10.4037/ccn2016420.

- Toy EC, Klamen DL. Alcohol withdrawal. In: Case Files: Psychiatry. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020:400-405.

- Lodewijckx E, Debain A, Lieten S, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for hypoactive delirium in adult patients: a brief report of the literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(6):1313-1316.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.037.

Reviewed and Edited By

Arif Alper Cevik, MD, FEMAT, FIFEM

Prof Cevik is an Emergency Medicine academician at United Arab Emirates University, interested in international emergency medicine, emergency medicine education, medical education, point of care ultrasound and trauma. He is the founder and director of the International Emergency Medicine Education Project – iem-student.org, chair of the International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) core curriculum and education committee and board member of the Asian Society for Emergency Medicine and Emirati Board of Emergency Medicine.

Sharing is caring

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print