by David Brian Wood

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female with no past medical problems presents to the emergency room complaining of 2 days of a red, itchy and burning left eye. She notes that she has had a lot of watery discharge during this time and that her vision is blurry on occasion but improves after blinking a few times. She works in a day care where many of the children have been sick lately. She does not use corrective lenses and does not recall any trauma to the eye. She also denies systemic symptoms such as fever, photophobia, or joint pain. Vitals: T 98.5oF, HR 78, BP 124/68, RR14, SpO2 100% on room air. Visual acuity: 20/20 in both eyes. Peripheral fields: intact. Forehead/maxilla: no erythema or swelling. Lids/lashes: left eyelid mildly swollen. Otherwise, lids and lashes are normal, and eversion of eyelid demonstrates no foreign bodies. Conjunctiva: conjunctiva on the left is diffusely injected, and there is watery discharge. Pupils: round, reactive to light, and equal bilaterally. Slit lamp: lids, lashes, and conjunctiva as above. No abrasions or lacerations visualized with fluorescein. Anterior chamber without cell and flare. Intraocular pressure: 18 mmHg bilaterally.

Critical Bedside Actions and General Approach

The initial step in the assessment is to determine if there is chemical exposure. The eye should be irrigated for at least 30 minutes or longer. If there has been exposure to an alkaline substance, irrigation can be stopped once the pH of the tears is neutral.

If there has been no chemical exposure, a thorough history and physical should be obtained. One practical approach is to first subdivide the etiologies into painful or painless.

Differential Diagnoses

Painful red eye

- If the eye is painful, break it down based on the anatomic structure involved.

- Cornea (abrasions, ulcer, keratitis, herpes simplex keratitis)

- Eyelid (internal hordeolum, chalazion, external hordeolum, blepharitis, HZ ophtalmicus, preseptal cellulitis)

- Conjunctiva (conjunctivitis, dry eyes, glaucoma)

- Ciliary or scleral (scleritis, episcleritis)

- Anterior chamber (anterior uveitis/iritis, endophtalmitis, hyphema)

- Posterior chamber—usually does not cause a red eye and is more likely to interfere with vision or cause deep dull pain.

Painless red eye

- If the red eye is painless, determine if the erythema is localized or diffuse.

- Diffuse- usually caused by an eyelid issue such as blepharitis, ectropion, trichiasis, entropion, stye, or tumor.

- Localized- based on the structure involved. Examples include subconjunctival hemorrhage, trauma, corneal foreign body, chalazion, and pterygium.

History and Physical Examination Hints

A thorough history should be obtained by paying particular attention to the following:

- Trauma to the face or eye (including possible foreign bodies)

- Pain and the specific location of the pain

- Photophobia

- Pain with extraocular movements

- Change in vision

- Systemic symptoms including fever, URI symptoms, weight loss, or joint pain

- History of inflammatory disease (SLE, MS, ankylosing spondylitis, etc.)

The patient’s description of eye sensation can also help with the evaluation of the red-eye.

- Itching/burning: conjunctivitis, dry eye syndrome, or blepharitis.

- Foreign body sensation: corneal irritation or inflammation

- Sharp pain: anterior chamber process such as keratitis, uveitis, acute angle-closure glaucoma

- Dull pain: increased intraocular pressure or an extra orbital process

Concerning findings on history:

- Severe ocular pain

- Persistently blurred vision

- Soft contact use-more susceptible to bacterial infection

- Immunocompromise

The ocular examination has numerous components, requires particular technical skill and therefore should be approached systematically so that no part of the exam is overlooked.

One approach to examining the eye is for the examiner to begin peripherally and progress inward, ending with the fundoscopic examination as shown below: Order of Exam

- Visual Acuity : Remember to test each eye with and without corrective lenses. If they do not have corrective lenses, a pinhole can be used which will correct most refractive disturbances. If vision is too poor to read an eye chart, assess if the patient can detect the following: count fingers, detect hand motion, any light perception.

- Peripheral fields

- Extra-ocular eye movements: Look for disconjugate gaze and ask if the patient develops any diplopia when looking in a certain direction. Either of these findings suggests an entrapped extraocular muscle or nerve deficit.

- Surrounding structures (forehead and maxilla): Assess for surrounding erythema, induration, or rash.

- Eyelids and lashes: Remember to evert the eyelids as well. Look for localized swelling or redness.

- Conjunctiva

- Pupils: Note the size, shape, symmetry, clarity, and reactivity to light. Assess for an afferent papillary defect (APD) using the swinging flashlight test. If the pupil dilates when the light is shining in it, that eye has and APD and is not transmitting as strong of a response to the light compared to the opposite eye. An APD can be caused by many problems including vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, or optic neuritis.

- Slit lamp exam: Re-examine the lids, lashes, conjunctiva, and cornea.

Use fluorescein to evaluate for foreign bodies, abrasions, lacerations, or Siedels sign (streaming of aqueous humor from punctured globe site). Always have the patient move the eyes in all directions to visualize the entire conjunctiva. Visualize the anterior chamber to look for cell and flare, white blood cells (hypopyon), or red blood cells (hyphema). - Intraocular pressure assessment: Do not measure if there may be a penetrating injury as this would exacerbate aqueous humor leakage.

- A pressure of 10-20mmgHg is considered normal.

- A pressure >20mmHg warrants an ophthalmology consult.

- Pressures >30 necessitate rapid treatment of underlying etiology (lateral canthotomy for retrobulbar hematoma or medication administration for acute closed-angle glaucoma).

- Fundoscopic exam: Often difficult to do a thorough exam in the emergency department, as the eye is typically not dilated.

The application of topical anesthetics to the eye helps to differentiate between superficial and deeper causes of pain. Pain that is not completely relieved by topical anesthetics is more likely to be from the sclera or anterior chamber.

Emergency Diagnostic Tests and Interpretation

Laboratory tests

In most cases, laboratory tests are rarely indicated or of much utility. If there is a concern for an underlying autoimmune disorder or temporal arteritis erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels can be assessed.

Imaging

The two most common scenarios of obtaining imaging of the red eye include facial fracture and penetrating foreign body. Plain radiographs can be obtained to assess for facial fractures. However, CT of the facial bones has replaced this imaging modality as it is more sensitive and specific for fractures. If there is a concern for a penetrating foreign body, a CT of the orbits can also be obtained. An MRI is an excellent modality for assessing foreign bodies but is contraindicated if there is any concern that the object may be metallic.

Emergency Treatment Options

As stated previously, any eye that has come into contact with a chemical should be irrigated with 1-2L of NS until the pH of tears has returned to neutral. If there is a concern for retrobulbar hematoma and the intraocular pressure is >40mmHg, a lateral canthotomy should be performed. If neither of these conditions exists then treatment can be tailored to the specific diagnosis.

Painful Red Eye

Cornea

Corneal abrasions

A corneal abrasion after staining with florescine. By James Heilman, MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11918476

- Most corneal abrasions will heal rapidly independent of intervention. Treatment focuses on preventing secondary infection and controlling pain. A significant component of the pain from a corneal abrasion comes from ciliary spasm that can be relieved by topical cycloplegics.

- Cyclopentolate is a short acting agent, Repeat every 4-6 hours.

- Homatropine is a long acting. Its effect lasts 2 days.

- In addition, oral NSAIDs or opiates may be needed to control the pain adequately. To prevent secondary infection, topical antibiotic ointments can be used (below recommendations are adopted from Harwood-Nuss and Rosen). If the abrasion is large or crosses the central visual axis, the patient should follow up with ophthalmology within 24 hours. Otherwise, follow-up can occur within 72 hours to ensure the abrasion is healing.

- Antibiotics

- Gentamicin ointment/solution 0.3%

- Ciprofloxacin solution 0.3% – Effective against Pseudomonas; prescribe to contact lens wearers

- Erythromycin ointment 0.5% – Effective against Pseudomonas; prescribe to contact lens wearers

- Ofloxacin 0.3%

- Polymyxin/trimethoprim

- Antivirals

- Trifluridine 1%

- Vidarabine 3%

- Antibiotics

Corneal ulcers

Corneal ulcer with circumcorneal congestion. Photo: P Vijayalakshmi

- Corneal ulcers are more serious and can pose a significant threat to the patient’s vision. Ophthalmology should be consulted emergently for cultures of the ulcer and initiation of antibiotics as well as, in certain cases, antifungals.

Herpes Simplex Keratitis

Herpes simplex virus Top left: Child with measles and severe herpes simplex keratitis affecting the right eye. Top right: Dendritic ulcer stained with fluorescein dye Bottom left: Geographic ulcer stained with fluorescein dye Bottom right: Inflamed conjunctiva and geographic ulcer Photo (clockwise from top-left): John Sandford-Smith, Allen Foster, David Yorston)

- Herpes Simples infections can be diagnosed based on its characteristic dendritic pattern seen with fluorescein staining. Conjunctival infections can be treated with trifluridine one drop up to nine times per day and antibiotic ointment such as erythromycin can be added to prevent secondary infections. All patients for which there is a concern for herpes keratitis should be seen by an ophthalmologist within 48 hours.

Eyelid

Internal/External hordeolum and acute chalazion

Chalazion © International Centre for Eye Health http://www.iceh.org.uk, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Initial treatment for these conditions consists of warm compresses and erythromycin ointment twice daily for 7-10 days. Referral to ophthalmology as an outpatient can be made if symptoms do not improve after 1-2 weeks of treatment.

Acute Blepharitis

Posterior blepharitis © John KG Dart

- Blepharitis is caused by inflammation of an eyelash follicle due to an overgrowth of bacterial skin flora. The mainstay of treatment consists of daily cleaning of the edge of the eyelashes.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus Photo: John Sandford-Smith

- Patients with herpes zoster ocular infections should be treated with artificial tears and erythromycin ointment to prevent secondary infection. Oral antiviral medication can be used if there is skin involvement and, after consultation with an ophthalmologist, topical antivirals may be prescribed as well. The significant pain from herpes zoster infections may require opiate treatments or the use of an antidepressant such as amitriptyline 25mg P.O. TID.

Conjunctiva

Acute closed-angle glaucoma

Acute glaucoma, red eye. Photo: International Centre for Eye Health http://www.iceh.org.uk, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- The overall goal is to reduce intraocular pressure by decreasing aqueous production and increasing outflow. Aqueous outflow is improved through miosis as this pulls the iris away from the trabecular meshwork. Definitive treatment is an iridectomy performed by an ophthalmologist.

-

Acute closed-angle glaucoma and IOP lowering agents can be devided into 2 category (adopted from Tintinalli)

-

Topical agents

-

Timolol – 0.5% 1 gtt q5min x3 doses then 1gtt q12h, decreses production of aqueous humor. Should be avoided in patients with asthma, heart block, and heart failure.

-

Pilocarpine – 2% 2 gtt q5min until pupil constricts. Then 1gtt q6h. It is outflow parasympathetic agonist, causes myosis. Rarely causes sweating, bradycardia, hypotension.

-

Apraclonidine – 1% – 1gtt q5min x3 doses. Decreases production of aqueous humor (alfa-2 agonist). Used most often in chronic glaucoma but may be useful in AACG.

-

Latanoprost – 0.005% 1gtt daily. Increases outflow.

-

-

Systemic agents

-

Acetazolamide – 500mg IV q12h or 500mg PO q6h. It is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. Decreases production of aqueous humor. It should be avoided in patients with respiratory disease as it causes respiratory acidosis.

-

Mannitol 20% – 1-2 gram/kg IV over 30-60 minutes. Decreases Aqueous humor by increasing serum osmolality.

-

-

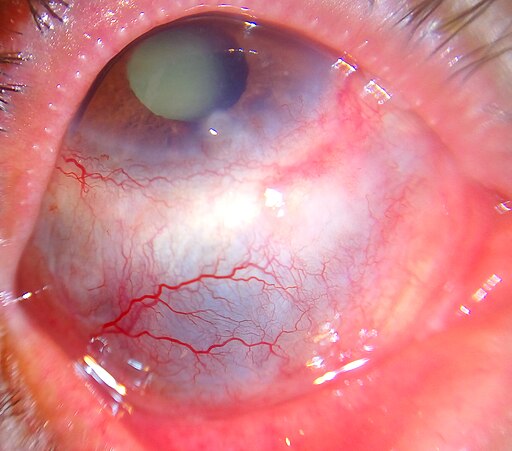

Conjunctivitis

By Rbmorley – Robert Morley, Public Domain, Link

- Most cases of conjunctivitis will be due to allergic or viral causes and can be treated with artificial tears 5-6 times per day. If there is a concern for a bacterial cause of conjunctivitis the patient can be treated four times daily for 5-7 days with topical antibiotic drops such as trimethoprim or polymyxin B. If the patient wears soft contact lenses, then Pseudomonal coverage is necessary with a fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside.

Ciliary/scleral

Episcleritis

- Artificial tears can be used up to four times per day to help lubricate the eye. A trial of oral NSAIDs can be given in the emergency room and if pain resolves can be continued as an outpatient. If the patient continues to have significant pain after NSAID a topical steroid can be used to relieve the discomfort. The steroid drops can be continued as an outpatient until seen by ophthalmology in 2-3 weeks.

Scleritis

By Imrankabirhossain – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

- Oral NSAIDs can be used for pain control as in episcleritis. Topical steroids are ineffective in scleritis, however, and oral steroids may be used starting at prednisone 60mg daily for 1 week and a slow taper over the next 4-6 weeks. Ophthalmology should be consulted and may recommend starting additional immunosuppressive agents.

Anterior chamber

Uveitis/Iritis

Acute anterior uveitis 45-year-old female. Complains of painful eye and discomfort in bright light with watery discharge. VA 6/12. Photo: International Centre for Eye Health http://www.iceh.org.uk, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Often related to a systemic process such as a rheumatologic condition, malignancy, or infection. Iritis and Uveitis can be treated symptomatically with cycloplegics, which paralyze the ciliary body and pupillary sphincter. A long-acting agent such as homatropine will last for 2-3 days after one dose and can control the pain until the patient can be seen by an ophthalmologist. These patients should be seen by an ophthalmologist within 48 hours.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis with extensive hypopyon consistent with active infection. © International Centre for Eye Health iceh.lshtm.ac.uk, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Usually leads to vision loss and therefore requires an emergent ophthalmology consult. Admission is necessary to administer IV antibiotics. In addition, the ophthalmologist may aspirate the vitreous and administer intraocular antibiotics and steroids.

Hyphema

By Rakesh Ahuja, MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, Link

- Initial treatment consists of elevating the patient’s head to allow the red blood cells to settle inferiorly where they are less likely to obscure the trabecular meshwork and raise intraocular pressure. If intraocular pressure is increased >30mmHg, the same treatment options can be employed as described in glaucoma. Patients with hyphema should have ophthalmology consult in the ED.

Others

- Retrobulbar hematoma

- In patients in which there is a concern for retrobulbar hematoma or other space-occupying retro-orbital lesions in which the intraocular pressure is >40mmHg, a lateral canthotomy should be performed to relieve the pressure and spare the optic nerve from further damage. If a retrobulbar hematoma is present, but the intraocular pressure is below 40mmgHg, and there is no vision loss, ophthalmology should be consulted. Similar medications to those used in acute closed-angle glaucoma can also be used to help decrease the intraocular pressure.

Painless Red Eye

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

By Daniel Flather – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

-

- No treatment is necessary for a subconjunctival hemorrhage as the blood will resolve within 2 weeks.

Pterygium

By The Photographer – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

- The management of a pterygium focuses largely on preventing it from enlarging through the use of sunglasses or goggles to prevent ultraviolet light, dust, and other irritants. If the pterygium is inflamed, artificial tears can be used four times per day. For severe inflammation, topical steroids can be used (below recommendations adopted from Harwood-Nuss) or topical NSAIDs. Surgical removal by an ophthalmologist may be indicated if the visual axis is impaired or for persistent irritation.

- Topical steroids

- Prednisolone acetate 0.125% – Potent. Effective for anterior chamber inflammation

- Medrysone 1% – Mild potency. Use for allergies

- Rimexolone 1% – Mild potency

- Dexamethasone 0.1% (solution), 0.05% (ointment) – Potent

- Topical steroids

Corneal foreign body

Corneal foreign body This is a ‘rust ring’ which shows signs of having been present for some days. The iron particle or ‘rust’ will lift off the cornea easily but will leave a stained area beneath. Removal with a needle or drill (burr) will be necessary

- If a small corneal body is seen on the exam with the slit lamp, the eye should first be anesthetized prior to removal with a topical anesthetic. The foreign body can then be removed using a small-gauge needle, fine forceps, or irrigation. A metallic foreign body will usually leave a rust ring that should be removed with an ophthalmic burr if available. After the foreign body is removed, the resulting defect can be treated as a corneal abrasion with topical antibiotic ointment.

Procedures

While rare, the main ophthalmologic procedure performed in the emergency department is a lateral canthotomy. The overall goal of the lateral canthotomy is too severe the connection between the bony orbit and lower eyelid to allow the orbit to move forward to compensate for the increased pressure placed on it. To perform a lateral canthotomy the canthus is first anesthetized, then crushed with curved forceps, and then cut with scissors. The inferior canthus tendon can then be identified by strumming it with the scissors and can then be incised. Following severing the tendon, the inferior eyelid should be released completely from the orbit. Depending on the amount of time the retina was ischemic, there may be rapid improvement in vision as the pressure is reduced.

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric patients suffer from many of the same etiologies of red eyes as adults but may be more difficult to obtain an adequate exam on. Visual acuity in children begins around 20/100 and improves to 20/20 by approximately 8 years of age. Before 5 years of age, most children will be unable to read a Snellen chart. Visual acuity can be grossly tested by covering each eye separately and having the child fixate on an object of interest. If the vision is normal, the child will continue to fixate on the object. By around 3 years old visual acuity can be tested more effectively using an Allen chart or Tumbling E chart.

Neonatal conjunctivitis is usually caused by exposure to an infectious agent while exiting the birth canal. Most commonly neonatal conjunctivitis is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoea but can also be due to herpes simplex virus. Treatment is based on the incubation period as shown below (adopted from Harwood-Nuss). In addition, neonates with HSV will require ophthalmology consultation. HSV and gonococcal conjunctivitis will require inpatient therapy with ophthalmology serving as a consult.

- N. gonorrhoeae has 2-7 days incubation period. Ceftriaxone 25-50mg/kg IV or IM, once is effective for treatment. For prophylaxis, 1% silver nitrate, 0.5% erythromycin ointment, 1% tetracycline can be used.

- C. trachomatis has 5-14 days incubation period. Treatment is erythromycin 50mg/kg/day divided q.i.d. PO x14 days. There is no prophylactic agent recommendation.

- HSV has 1-2 weeks incubation period. Acyclovir 60 mg/kg/day divided q.i.d. for 2-3 weeks AND atopical anti-viral agent are used for treatment. There is no prophylactic agent recommendation.

Disposition Decisions

The vast majority of patients presenting for red-eye will be discharged home. Even many of the ocular emergencies will be able to be discharged following evaluation by ophthalmology. There are a few conditions requiring admission such as endophthalmitis, retrobulbar hematoma, and globe rupture. Disposition and urgency of consultation are covered in the above clinical management of ocular problems.

References and Further Reading

- Nickson, C. The Red Eye Challenge: Life in the Fast Lane. Available from: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/the-red-eye-challenge/. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.

- Sharma R, Brunette DD. Ophthalmology. In: Marx JA. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2014: 909-930.

- Wrist JL, Wightman JM. Red and Painful Eye. In: Marx JA. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2014: 184-197.

- Walker RA, Srikar A. Eye Emergencies. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. New York: McGraw Hill, 2011. 1-80.

- Alteveer JG, McCans K. Eye Disorders. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 1227-1237.

- Bozeman W, Everett RS. Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 365-370.

- Kramer DA, Bohrn MA, Vega DD. Acute Eye Infections. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 361-365.

- Loo TC. Acute Eye Infections. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 355-358.

- Porter RS. The Red Eye. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 341-344.

- Platts-Mills TF. The Eye Examination. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 346-349.

- Sawtelle S. Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005: 358-63.

- Schertzer, K. Mahadevan, S. Common Ophthalmic Medications. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 342-346.

- Weichenthal LA. Corneal Abrasion and Forein Bodies. In: Wolfson AB, Harwood-Nuss A. Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 349-351.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Corneal and Conjunctival Foreign Bodies. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 17-19.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Episcleritis. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 121-122.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus/Varicella Zoster Virus. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 81-84.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Pterygium/Pinguecula. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 66-67.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Scleritis. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 122-125.

- Gersten AT, Rabinowitz MP. Traumatic Retrobulbar Hemorrhage. In: Ehlers JP, Shah CP. The Wills eye manual: Office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012: 35-39.